The Big Day: White Abalone Captive Breeding at UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab

White abalone are the only marine invertebrate in the NOAA Fisheries Species in the Spotlight Initiative. The initiative, launched in 2015, aims to focus time, energy and resources on a set of nine critically endangered marine species, ranging from white abalone to Pacific Leatherback turtles.

In the wild, white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni) populations have not shown signs of recovery, despite the fact that all fishing for the species has been banned for over two decades. Abalone reproduce by releasing their gametes into the water column, a process known as broadcast spawning. This method of reproduction requires a certain population density to be successful, and there simply are not enough white abalone in the wild today for this to succeed naturally.

For white abalone, the Species in the Spotlight program facilitates and supports the long-term, coordinated partnerships required to recover the species. The next five year plan for the white abalone’s recovery was published April 21, 2021, outlining major priority actions to move towards the ultimate goal of species recovery. The major priority action for white abalone recovery hinges on the continued success of the lab-based captive breeding program, and the outplanting of these lab-born animals back into their native habitat - the waters of the Pacific from Point Conception, California to Punta Abreojos, Mexico.

Dr. Kristin Aquilino selects adult white abalone broodstock for the spawning event. A combination of 22 captive-bred and 10 wild-collected abalone were selected for the day’s attempt. Wild white abalone were collected under the relevant state and federal permits.

Attempts in the early 2000’s to spawn white abalone in captivity in their native Southern California were successful, but keeping the captive animals healthy proved to be a challenge. The bacterium that causes withering syndrome, Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis, is distributed throughout the waters of the Pacific Ocean. In warmer water temperatures, the disease can be fatal. After much study, scientists have found ways to keep animals healthy even if infected, using antibiotic treatments and keeping water temperatures cool.

The UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab (BML) now acts as the headquarters for the breeding program for a variety of reasons, despite being outside the species range. Co-located with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife’s Shellfish Pathology Lab, BML has a unique combination of expertise, resources, and water quality to support white abalone breeding. Since 2012, the white abalone captive breeding program at BML has produced nearly 95,000 white abalone that have survived through their first birthday. To date, over four thousand captive-born white abalone have been returned to the Pacific, a process known as outplanting.

April 21st is my mother’s birthday, and according to her, it’s a good day to be born. This April 21st, I find myself pulling into the parking lot of the Bodega Marine Lab in the dark, pre-dawn hours. I am here at 5:45 AM, 500 miles from home and 300 miles outside the white abalone’s geographic range, hoping to witness the birth of the newest generation of white abalone.

The greenhouse on the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab campus where the spawning was held, to accommodate for social distancing. Jen McNealy and Shelby Kawana of BML transport the cart containing the 32 white abalone selected for the spawning attempt to the greenhouse.

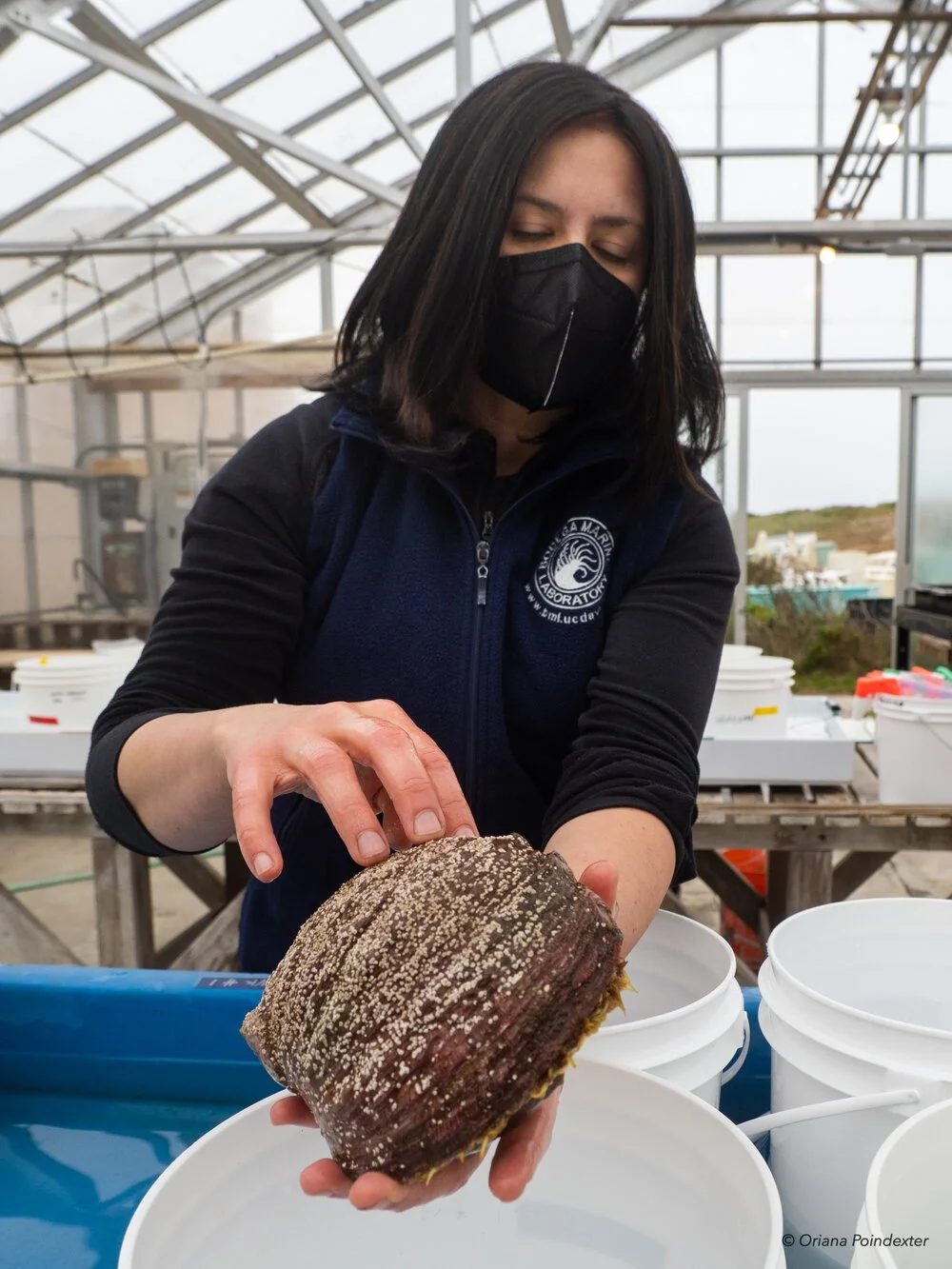

Dr. Kristin Aquilino, director of the white abalone captive breeding program at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab, places one of the captive-bred broodstock white abalone into its designated bucket for the spawning event.

At 6:00 AM on this auspicious morning, Dr. Kristin Aquilino, the lead scientist for the white abalone captive breeding program, is elbow deep in a tank of 57°F seawater, using a plastic spatula to dislodge adult white abalone from the tank walls. Today’s broodstock lineup is a mix of 10 wild-born and 22 captive-bred animals. She pulls each animal out, records the tag number and sex, and places them into bins full of seawater on a wheeled cart for transport to a nearby greenhouse.

Today’s action is set to happen in the campus greenhouse instead of the climate-controlled lab to accommodate for social distancing. The greenhouse is spacious, airy, and as the sun rises today, still quite cold. There are 32 white buckets prepped, filled a third of the way with a mixture of fresh seawater, dilute hydrogen peroxide, and a buffering solution. Each abalone gets their own bucket.

There’s tension in the air. I try not to project too many hopes onto these snails, and I sense the other humans in the room feel similarly. After all, there is a distinct possibility that nothing happens today in the greenhouse. This team attempted a spawning event with these animals in late March 2021 - with no success. It’s difficult to resist cracking jokes about stage fright, especially after I learn it is the male of the species that has recently been underperforming.

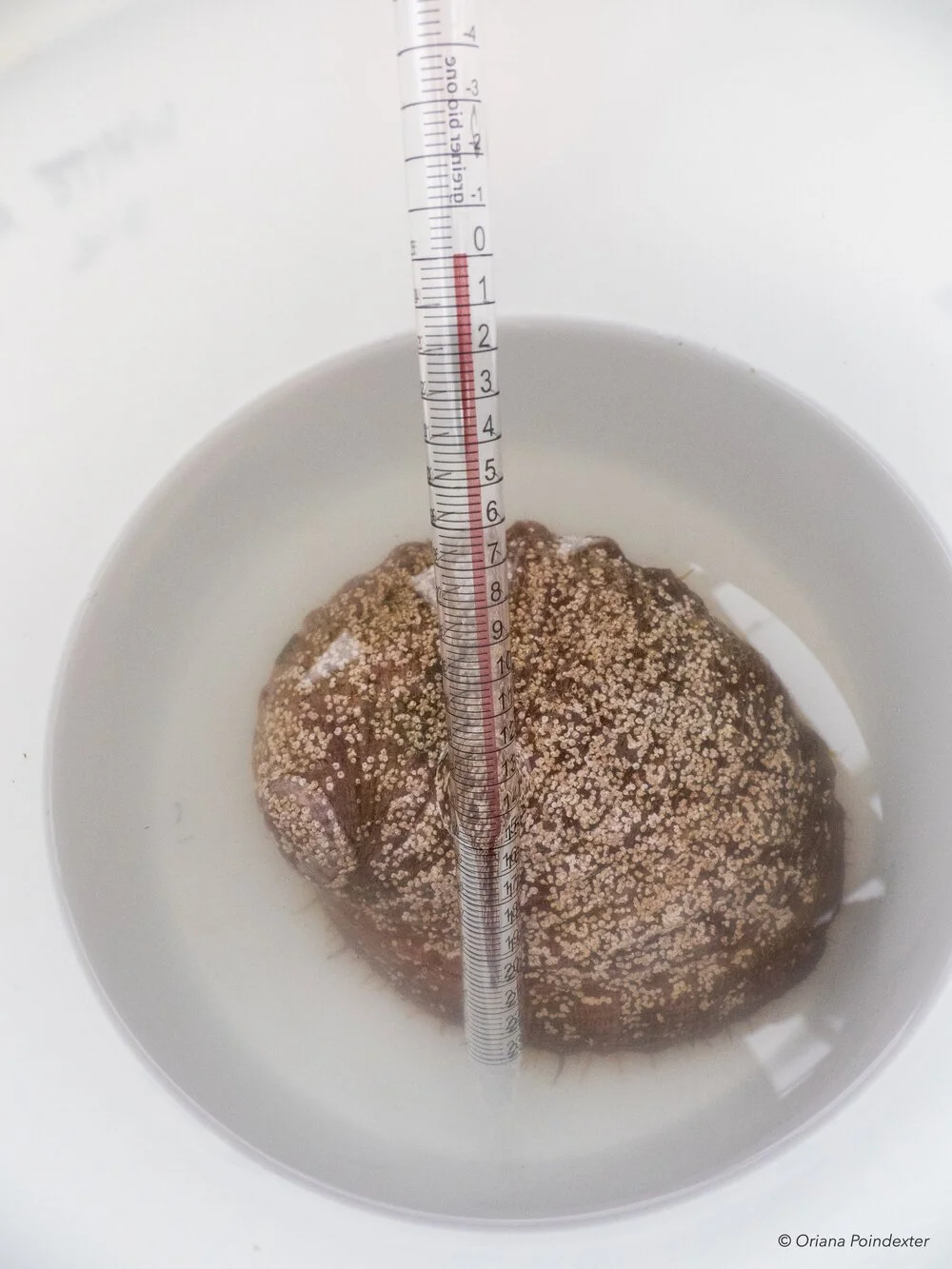

The abalone are placed in their private buckets at 7 AM. The hydrogen peroxide solution that encourages spawning can take from three to six hours to do the trick. In the meantime, each abalone is treated to an ultrasound, just like a pregnant woman.

Dr. Sara Boles, a postdoctoral researcher at BML, is developing ultrasound technology as a non-invasive method to determine if an abalone is ready to spawn. An abalone’s gonad, the reproductive organ that produces eggs or sperm, is a cone shaped organ that wraps around the digestive gland.

Clad in a wetsuit from the waist up to handle the animals in the cold water, Dr. Boles presses the ultrasound wand to the abalone’s body to view the thickness of the gonadal tissue. The working hypothesis is the thicker the gonadal tissue, the more prepared the animal is to spawn. When she spots a"five," the highest category for reproductive capacity, we take turns squinting against the glare of the greenhouse to see the parent's potential on the ultrasound’s screen.

Dr. Sara Boles performs an ultrasound on an adult white abalone prior to the day’s spawning attempt. She is developing this as a non-invasive technique to determine reproductive status in abalone. The ability to determine reproductive readiness and select the ripest animals for spawning may aid the production capacity of the white abalone captive spawning program going forwards.

The old-fashioned method to assess abalone sex and reproductive status is by visual inspection. With adult white abalone it is particularly difficult to determine sex and readiness visually, as the color variation between male and female animals is not as pronounced as in other abalone species.

After the ultrasounds, the abalone rest in their private buckets of aphrodisiac. The greenhouse brightens with the rising sun, though the campus is still cloaked in the white fog of the coastal marine layer. I pace around the 32 buckets, peering inside while learning more about the process from Dr. Aquilino and her team.

All of a sudden – it’s happening. At 9:51, a veteran wild born female starts the action by releasing just a few eggs. At 10:00, a captive-bred female tagged Green #397 joins, releasing a thin stream of light brown, spherical eggs through the open pores on her shell. Blythe Marshman of the CDFW Shellfish Health Lab, grabs their buckets and unceremoniously dumps them out, eggs and all. Ironically, the hydrogen peroxide solution that induces spawning also sterilizes the eggs and sperm, so the team must quickly replace the hydrogen peroxide solution with fresh seawater as soon as spawning is observed.

In clean seawater, female Green #397 continues to contribute to the future of her species. I wasn’t sure what to expect this morning before I arrived – but I’m impressed with what I’m seeing. The initial trickle of eggs gives way to a sputtering firehose and the tiny brown spheres cloud the seawater. The female is nicknamed Krakatoa as her bucket fills with eggs.

The greenhouse heats up. A captive-bred male tagged Green #305 begins to release sperm. His bucket is quickly dumped and refilled with clean seawater. Evan Tjeerdema, a BML lab tech, begins to siphon the white clouds of sperm. He’s trying to get the highest concentration of sperm by siphoning as closely to the animal’s open pores as possible. He uses a long pipette to transfer the liquid from the bucket to a vial, labels it with the time and animal’s tag number, then jams the vial upright into a nearby tub of ice.

The female tagged ‘Green 397’ released millions of eggs into her bucket throughout the day. The eggs are visible to the naked eye as tiny beige spheres, and are negatively buoyant.

The male tagged ‘Green 305’ was the only sperm donor for the day. He is pictured here in his bucket, with sperm lightly clouding the water, and the pipette used to transfer his genetic material for the fertilization process.

The team at BML is providing in vitro fertilization (IVF) service for white abalone. Krakatoa and her bucket of eggs is whisked away to the climate-controlled lab, along with the iced vial of sperm from male Green #305. For this part of the process, consistent temperatures are more critical, and the greenhouse keeps heating up as the day progresses.

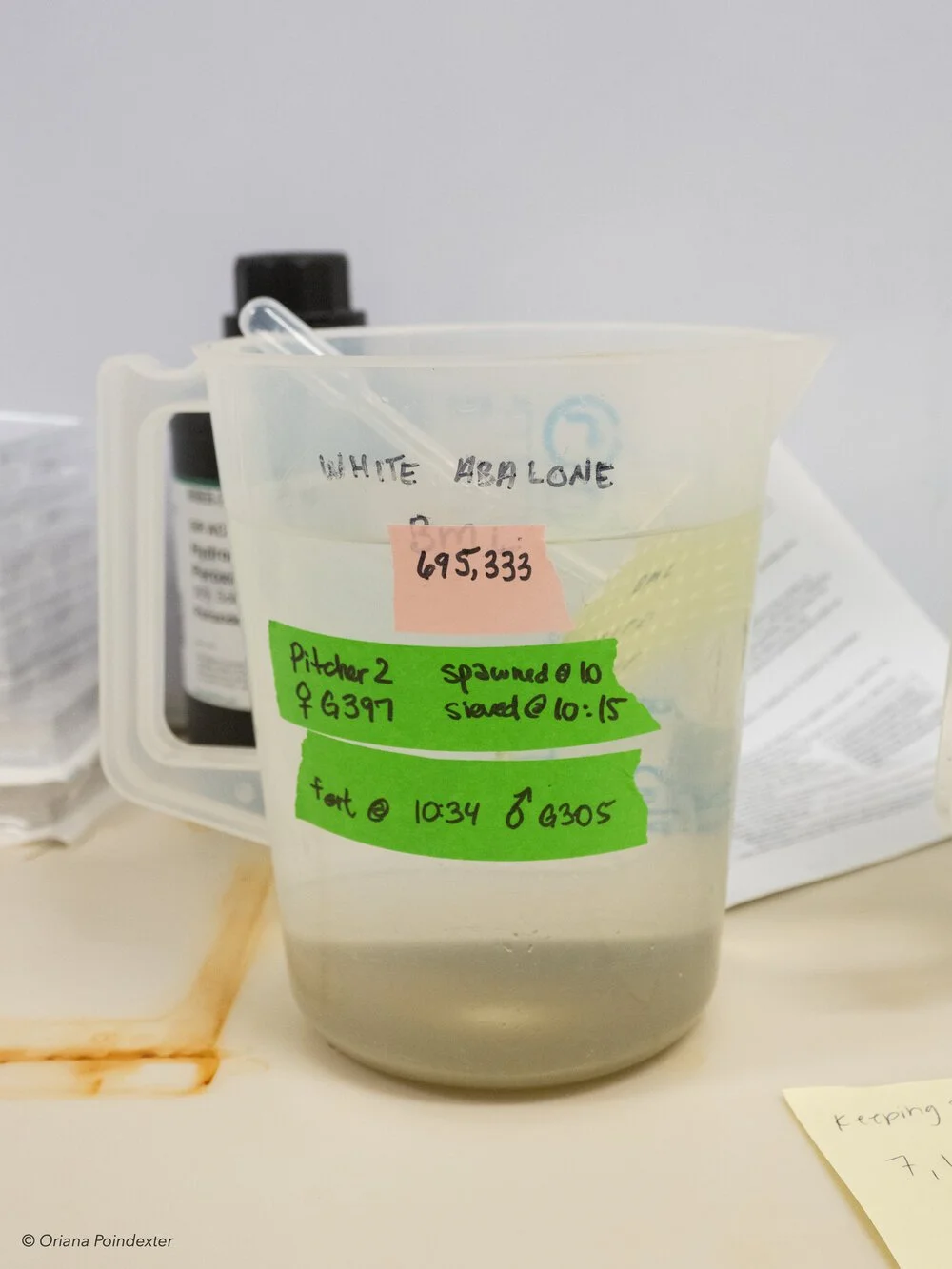

Dr. Aquilino and her team are the wizards behind the curtain here. A few eggs are pulled from the female’s bucket and placed on a microscope slide to check they are perfectly spherical. The sperm from the vial is also checked for quality and motility under the scope. Carefully measured quantities of sperm and eggs are combined into a series of small pitchers, aiming for a ratio of 10 visible sperm for each egg. It isn’t the slightest bit romantic.

Back in the greenhouse, there’s more action. Four more females join in on the spawning, one exuberantly and the rest more modestly. Green #305 continues to perform, releasing a bit more sperm for the vials. The moms-to-be are taken to the lab, where their eggs are checked and then combined with Green #305’s sperm in measured proportions, each pitcher marked with the names of the parents. The pitchers are gently, continuously, agitated, as the eggs will sink to the bottom if the water remains still. Ideally, in these pitchers, sperm will fertilize eggs and complete the second critical step of the day.

Even with all the effort and preparation, just six of the 32 animals staged today actually spawned. Green #305 was the only sperm donor, making this year’s cohort of white abalone entirely dependent on his genetic material. It better be good. By 2 PM, the action is called, and the 26 abalone that didn’t perform are returned to their tanks. Their big day is over.

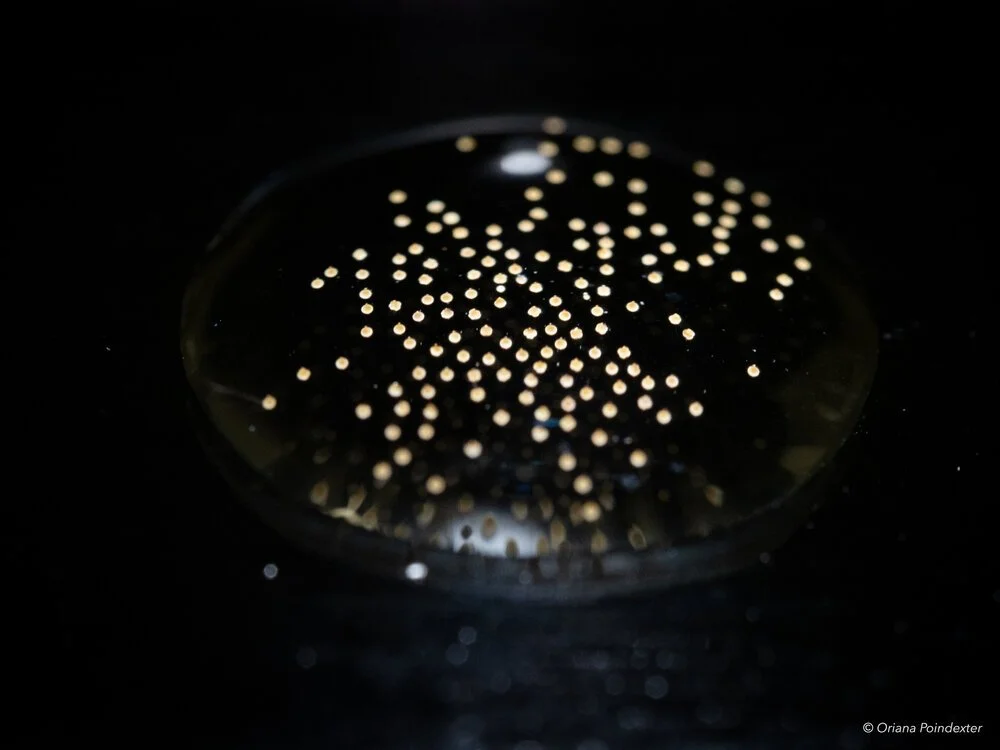

I am transported back to my high school biology lab as I squint into a compound microscope to see the fertilized eggs myself. Big enough to be visible to the naked eye, the eggs appear gigantic under the scope. The dark central yolk is surrounded by a translucent circle, making each egg look like a big round eye. It takes my eyes a few moments to register the sperm attached to the eggs, tiny flecks marring the smooth circle of the egg’s edge. By 3 PM, the fertilized eggs have begun to divide, morphing from big round eyes to four-leaf clovers. In 24 hours, they’ll hatch.

This morning, I was so wrapped up worrying whether spawning would happen that I hadn’t thought about what success would mean, logistically, for the afternoon. While I marvel at the new life created in the lab, Dr. Aquilino and her team activate a state-wide white abalone foster care network known as the White Abalone Recovery Consortium (WARC).

White abalone eggs are visible to the naked eye in a single drop of water on a microscope slide, illuminated from below by the scope’s light source.

Unfertilized (circular) and fertilized (clover shaped) white abalone eggs are seen under magnification through the dissecting scope. Fertilized abalone eggs hatch within 24 hours of fertilization.

Six white abalone collectively produced 5.7 million eggs today, far more babies than BML can care for on site as they grow. The WARC is a network of institutions throughout the state of California with the capacity to foster or otherwise support the white abalone captive breeding program, from embryo to outplant. A mix of academic, government, and private entities, the WARC partners are mostly based in Southern California, and these baby abalone need to get there quickly – ideally before they hatch. A few weeks ago, I visited one of these partners, the Aquarium of the Pacific, and met 4,000 one-year old white abalone that were born at BML last year. The majority of the eggs on today’s flight are heading to the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, where my office was located pre-pandemic. The aquarium staff at the La Jolla lab have been working hard in an otherwise empty lab to keep this program up and running, feeding and caring for the growing abalone every day.

Pre-pandemic, this meant a long day in the lab spawning abalone was followed by a long drive with a cooler full of embryos. With social distancing restrictions, it is no longer safe to have two staff members from separate households in the same vehicle for hours on end, traversing the state to distribute baby abalone. Today, there’s a private plane waiting.

A pitcher containing nearly 700,000 white abalone eggs labeled with the names of the parents: the mother is female ‘Green 397’ and the father is male ‘Green 305’.

In the lab, the team prepares the abalone for their first flight. I watch, mind-boggled, as they slowly pour a pitcher of abalone embryos into – of all things – a zip-top plastic bag. They manage not to spill. Each bag is labeled with the names of each parent, the estimated number of eggs, and their destination.

A total of four million eggs are double bagged, swaddled in towels, and then carefully packed into a single, well-worn cooler. The cooler is carried out to a waiting pickup truck and lifted into the back seat. The team waves, goodbye and good luck.

At golden hour, I follow a silver CDFW truck driven by Dr. Laura Rogers-Bennett down the narrow, winding roads of Sonoma wine country. We’re headed from Bodega Bay to the Sonoma Jet Center, a small facility just north of Santa Rosa, CA. It’s a gorgeous drive, through rolling hills with light spilling through the trees. I wax poetic in my head, mulling over the events of the past twelve hours and the steep odds these abalone face.

At the airport, we meet Dr. John Baker, an affable, enthusiastic volunteer pilot. A medical doctor by trade, John volunteers his time and his plane through LightHawk, a non-profit organization that provides flights to environmental and non-profit organizations in need. He’s beaming, and can’t believe his luck. He’s never had this many passengers before!

An airport staff member lifts the cooler of precious cargo into the plane. It just barely fits into the space available. Dr. Baker straps them in and poses for a photo before he completes the final preparations for take off. Waving goodbye, he steps into his plane and takes off into the sunset, millions of endangered white abalone in tow.

These young white abalone are offspring of the white abalone captive breeding program, born and raised at BML. With limited capacity to grow animals to size, most of the young white abalone born in Bodega Bay are distributed to partners throughout the state of California to grow up before outplanting to the Pacific.

Abalone expert Dr. Laura Rogers-Bennett of BML and Dr. John Baker, the volunteer pilot with LightHawk, pose for a photo with the cooler holding the flight’s passengers, four million endangered white abalone eggs. The flight’s passengers are headed to Southern California to grow up in labs and aquariums, including NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center, the Aquarium of the Pacific, The Bay Foundation, and The Cultured Abalone Farm.

Read more about white, black, red, pink, and green abalone in The Iridescent Ones blog series here.

Visit NOAA Fisheries to read more about endangered white abalone and current conservation efforts for this Species in the Spotlight. Learn more online about White Abalone Recovery Consortium and the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab.

Thank you to the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation for continued support of this work.

References

NOAA Fisheries. Endangered Species Conservation: Species in the Spotlight.

NOAA Fisheries. Species in the Spotlight: Priority Actions 2021-2025, White Abalone. 21 April 2021.

White Abalone Restoration Consortium. University of California Davis Coastal and Marine Sciences Institute.

Lighthawk Conservation Flying. www.lighthawk.org.