Red Abalone Aquaculture: From Tank to Table at the Cultured Abalone Farm

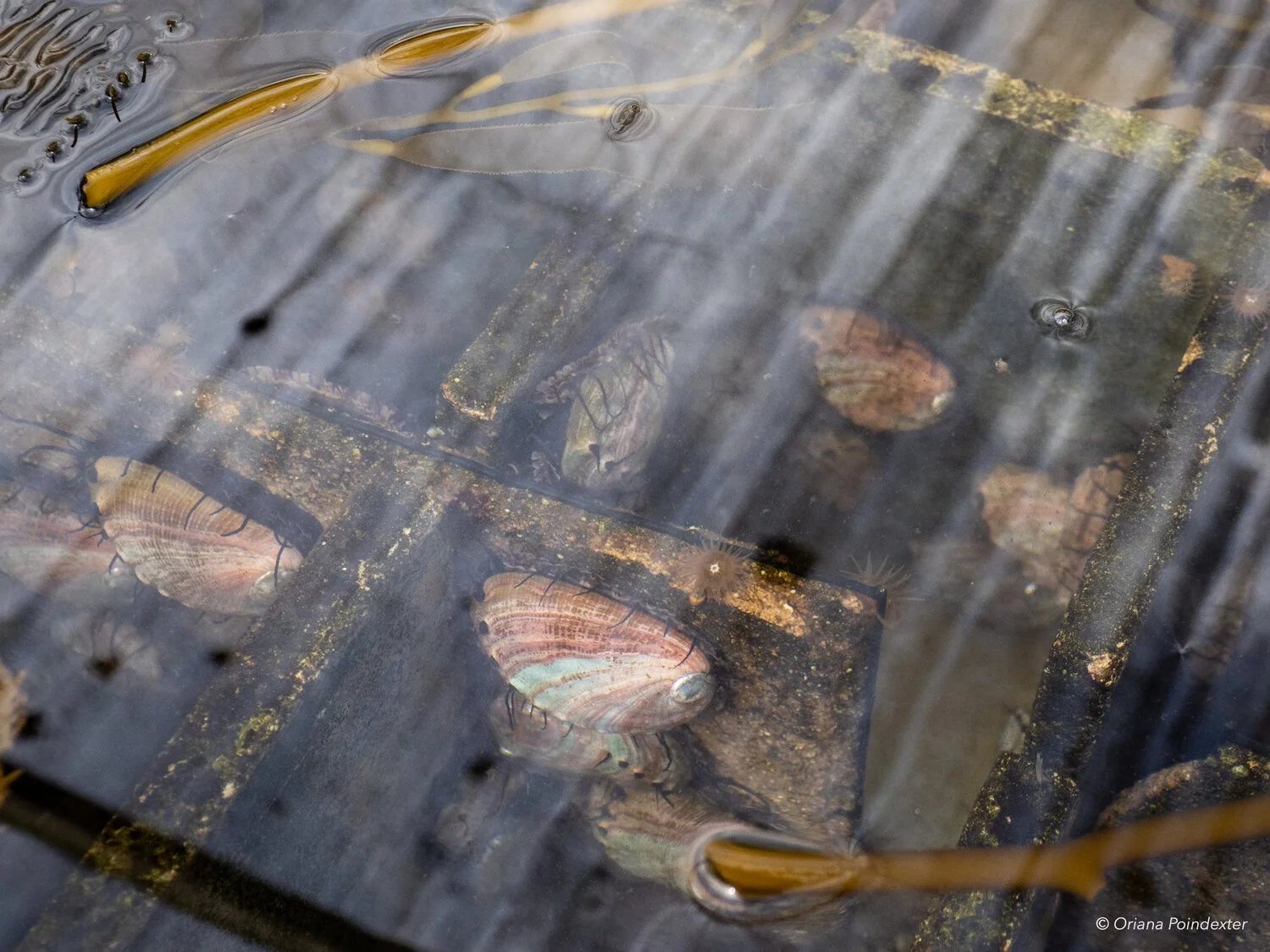

Red abalone (Haliotis rufescens) grow up to market size in their gridded tanks at the Cultured Abalone Farm. The banded pigments on their shells are the result of their varied diet of red and brown algae.

The Cultured Abalone Farm is nestled in a sun-dappled gully leading down to the ocean, just north of Santa Barbara. As we pull off the freeway onto the dirt road leading down to the farm, we are greeted by a truly impressive tree and a bright eyed puppy named Parker, who announces our arrival. I’m visiting The Cultured Abalone Farm to learn how seafood lovers can eat abalone in a responsible manner.

Abalone are an iconic and beloved seafood species on the Pacific coast. Native coastal people harvested abalone for thousands of years, using the meat for food and crafting regalia and tools from the shells. Shell middens found on the Channel Islands provide evidence of this long-term harvesting relationship, with one midden on Santa Rosa Island containing 7,000 years worth of abalone shells [1], collected from the waters of what is now designated as the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary.

Commercial fisheries for abalone in California began in the mid-1800s when Chinese immigrants began drying and exporting abalone collected from the shoreline, followed by Japanese divers who harvested abalone underwater.

It took some time for European immigrants in California to realize just how tasty the abalone was as food. An early celebrity chef, ‘Pop’ Earnest Doelter, did a good job convincing folks with his signature dish at his Monterey restaurant - schnitzel-style, fried and breaded abalone steaks [2]. For over a century, diving for abalone was a popular recreational activity along the California coast, with divers hauling out bags of abalone for beachside bonfires.

Given the current state of wild abalone populations off the California coast, aquaculture operations like The Cultured Abalone Farm are the only way to legally get an abalone onto your dinner plate in 2021. All California’s commercial fisheries for wild abalone have been closed since 1997. The last recreational abalone fishery in the state was closed in 2018 and will remain so through the year 2026 [3].

Parker’s barks bring out Devin Spencer, the Cultured Abalone Farm’s Hatchery Director. Her domain, the hatchery, is a busy place on the day of our visit, as she is nursing thousands of newborn red abalone. On land, abalone begin their lives in a bucket. We started our tour by peering into a series of white five-gallon buckets, which are filled about three-quarters of the way with seawater, clear with a light greenish tinge, and speckled throughout with what look like tiny sesame seeds at first glance. Each of the tiny specks is a baby abalone, just a few days old. There are millions in each bucket.

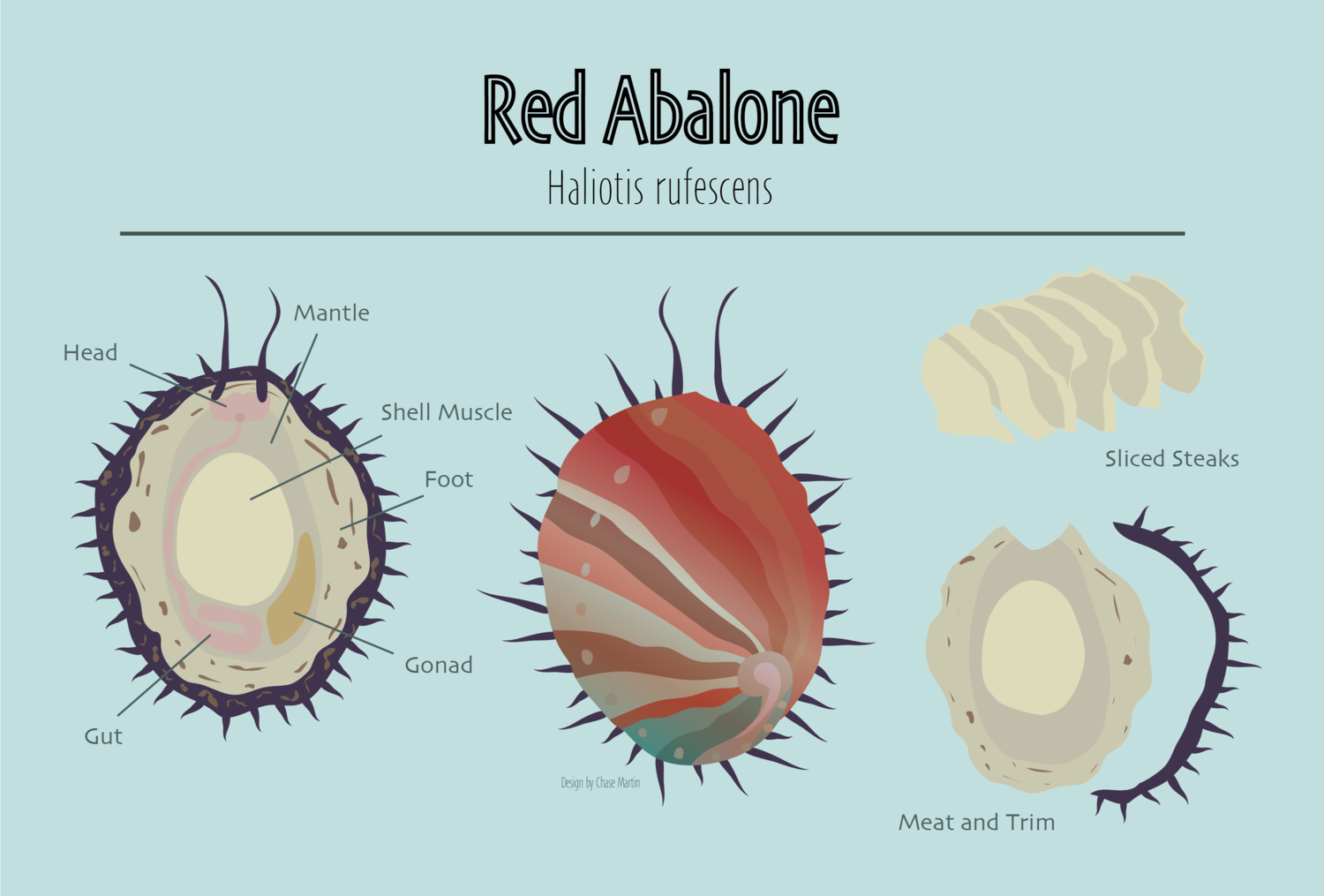

Here at the Cultured Abalone Farm, the babies are red abalone (Haliotis rufescens). The world’s largest species of abalone, H. rufescens can grow up to 12 inches in diameter and nearly 15 pounds in the wild, a truly massive snail. At the farm, they are grown up to about three inches in shell diameter. Given their clearly demonstrated success in the spawning and raising of abalone, the farm is also occasionally called upon to help out as a partner in the conservation efforts for the endangered white abalone (H. sorenseni) by housing, feeding, and growing out many thousands of offspring born from parents at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab.

The hatchery building is where young red abalone live from the time they are born until they’re ready for the outdoor tanks. The abalone in these tanks were just two weeks old at the time of my visit.

These babies have recently settled into the hatchery tanks, and are just starting to be recognizable to the naked eye as abalone.

Once they outgrow the hatchery, the young red abalone are transferred to larger tanks outdoors under sunshades, where they grow up to market size. We meet Doug Bush, the farm’s General Manager, outside near a truck filled to the brim with freshly harvested giant kelp.

Baby abalone eat diatoms and other microalgae, tiny algal species found in sea water. The Cultured Abalone Farm pumps water directly from the Pacific Ocean -- clean, cold, and full of nutrients for the growing abalone. Once the abalone grow to three to four millimeters in shell length, they start to eat macroalgae. At the farm, they are fed a combination of giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera), dulse (Palmaria spp), and ogo (Gracilaria pacifica).

Ogo and dulse are both grown on-site in outdoor tanks, but the giant kelp is actually harvested from the wild. Twice a week, a specially-designed vessel fitted with an aquatic lawn-mower trims the canopy of the giant kelp forests off of Santa Barbara, and delivers fresh kelp to the farm. Earlier that day, we had spotted the kelp harvesting vessel, F/V Ocean Harvest, steaming back into Santa Barbara Harbor. About an hour later, we saw the harvest – two truckloads filled to the brim with fresh, glistening giant kelp – being delivered to the thousands of hungry mouths at the farm.

Giant kelp grows like nothing else on earth – up to two feet per day in perfect conditions [4 ]. Doug explains that mowing the top of the kelp canopy doesn’t harm the organism or its reproductive potential. With a growth rate like that, the canopy can regrow what was trimmed within a week. A perennial species, giant kelp releases its spores from specialized blades near the base of the organism. This means trimming the tips of the giant kelp canopy has no detrimental effect on next year’s giant kelp forest. There are many factors that can have detrimental effects on next year’s giant kelp forest – but trimming the canopy for abalone food is not one of them.

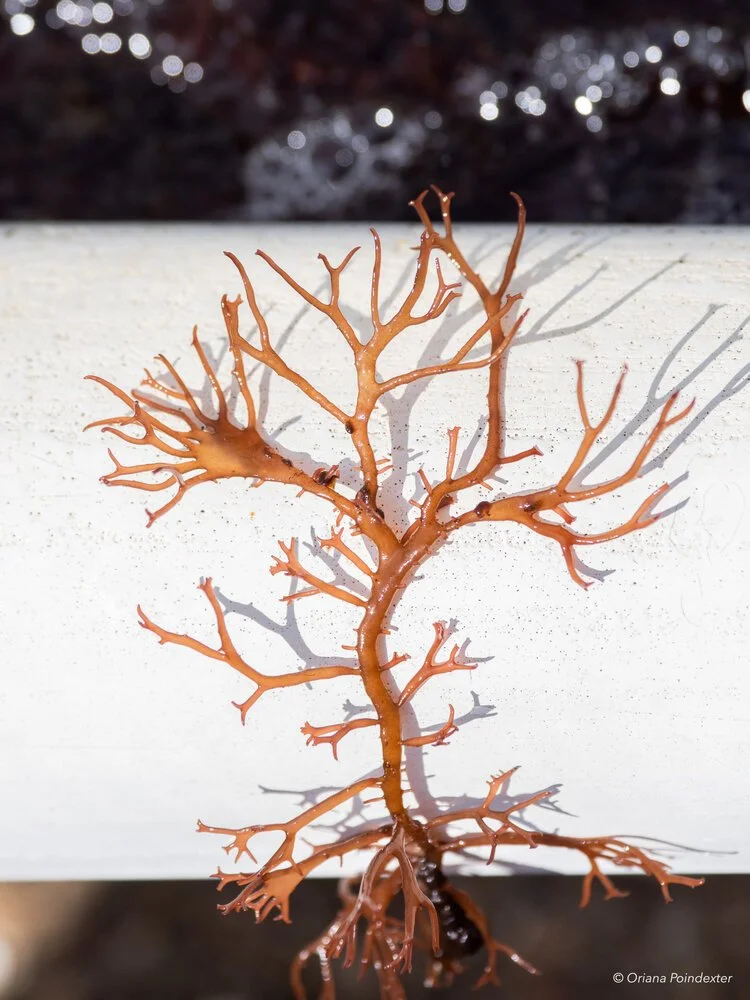

Abalone food: Dulse (Palmaria mollis) is a species of red algae native to the California coastline, along with red abalone. The Cultured Abalone Farm grows dulse on site as part of their abalone’s diet.

Abalone food: Fresh giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) arrives by the truckload. Harvested by a specialized kelp cutting vessel, the F/V Ocean Harvest, delivers twice a week to feed the growing red abalone.

Abalone food: Ogo (Gracilaria pacifica) also grown on site as part of the diet for red abalone. It is another red algae native to the California coastline, and is popular for human consumption as well - you may have tried it in a poke bowl.

The growing abalone are ready for their lunch. We watch as Doug drops a single blade, or leaf, of kelp into one of the tanks. Instantly, the small snails leap into action, tentacles in overdrive. By snail standards, at least. The lucky abalone directly under the blade reach out with their epipodia and the edges of their feet to grasp on to their meal, greedily pulling at the blade. The abalone just out of range reach their epipodia, antennae and feet, stretching their entire beings in the direction of the tantalizing smell of fresh kelp. They don’t have to wait long. The single blade was just an appetizer, and soon, the entire tank is covered with a layer of fresh kelp, with plenty to go around.

The abalone are housed in grids within their tanks, with lots of nooks and crannies to nestle into. Their shells are mostly free from encrusting organisms, although I do spot one abalone proudly sporting a stout orange anemone on its back. In the tanks, the abalone crawl over each other and eat the algae off each other’s shells between feedings, preventing the growth of the extravagant layer of algal camouflage that most of their wild cousins sport. Their tentacles are incredibly long, compared to what I see in the wild, and their shells are striped with pink, green, red and brown bands, the different pigments in their algal foods translated beautifully onto their backs.

Three years of regular feedings brings these animals to market size, or about three inches across. Most leave the farm in mesh bags of twenty pounds each, headed to restaurants, seafood wholesalers, fishermen’s and farmer’s markets, and even direct for home delivery.

However, some stay behind and keep growing in their gridded tanks. The Cultured Abalone Farm houses tanks of older, larger red abalone, which are kept as broodstock, the parents of future generations of farmed abalone. Doug has another role in mind for some of these older abalone – growing them out for years longer, until they reach the hallowed 10-inch diameter of a ‘trophy ab’. Ten-inch red abalone were coveted back when you could harvest them recreationally, with experienced abalone divers saving and proudly displaying the gargantuan shells. Doug is betting that a select group of customers might be willing to pay extravagant prices for a trophy size red abalone, even a farmed one, to recreate their memories of frying up giant, plate-sized abalone steaks.

Red abalone are a good species for sustainable aquaculture given their herbivorous diet and relatively sedentary lifestyles and fast growth (for an abalone). Reflecting this, The Cultured Abalone Farm is rated as a Best Choice by the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch Program, along with other abalone farming operations that grow their snails in seawater tanks [5].

A broodstock-sized red abalone munches on giant kelp. This animal has grown past market size, and is a prospective parent for the next generation of abalone - and maybe one day, will hit the 10 inch mark!

A market-sized red abalone reaches for fresh kelp in the outdoor tanks at The Cultured Abalone Farm.

Read more about white and black abalone in The Iridescent Ones blog series here.

Visit www.culturedabalone.com to learn more about The Cultured Abalone Farm, or to order live abalone direct to your door.

Farmed Red Abalone Informational Recipe Card

Created in partnership with the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation, the Cultured Abalone Farm, and NOAA Fisheries, this informational recipe card will teach you how to prepare farmed red abalone at home. All harvest of wild red abalone is prohibited in the state of California.

To download a PDF version of the guide, please click on the image below.

To download guides for other seafood species, visit FishfulFuture.com. To request a printed version of the card, please send an email request to pelagicprojects@gmail.com.

References

Braje, Todd J., et al. "Human impacts on nearshore shellfish taxa: a 7,000 year record from Santa Rosa Island, California." American Antiquity 72.4 (2007): 735-756.

Thomas, Tim. The Abalone King of Monterey:" Pop" Ernest Doelter, Pioneering Japanese Fishermen & the Culinary Classic that Saved an Industry. Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

California Department of Fish & Wildlife. Invertebrates of Interest: Abalone.

“Kelp Forests - A Description.” Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration.

Seafood Watch. Abalone, Haliotis Spp. Seafood Watch - Monterey Bay Aquarium, 8 Jan. 2017.